The hard-working town could honestly lay claim to being “The Rubber Capital of the World.” It drew thousands of workers through their gates every day to build tires and other rubber products.

One important newcomer to Akron was a young man named Vernon Smithers. Born in Beebee, Arkansas, Vernon was one of many people drawn to Akron because of its rubber industry.

The growth of the Akron rubber industry was not isolated. Around the same time these rubber companies were sprouting in Akron, an organization called the Research Association of British Rubber Manufacturers (RABRM) was founded in England. In the wake of the Great War, as World War I was called, numerous research organizations were founded to solve problems the war had raised around the world. This research organization, which would later change its name to Rubber and Plastics Research Association (RAPRA), would play a significant role in the Smithers story almost a century later

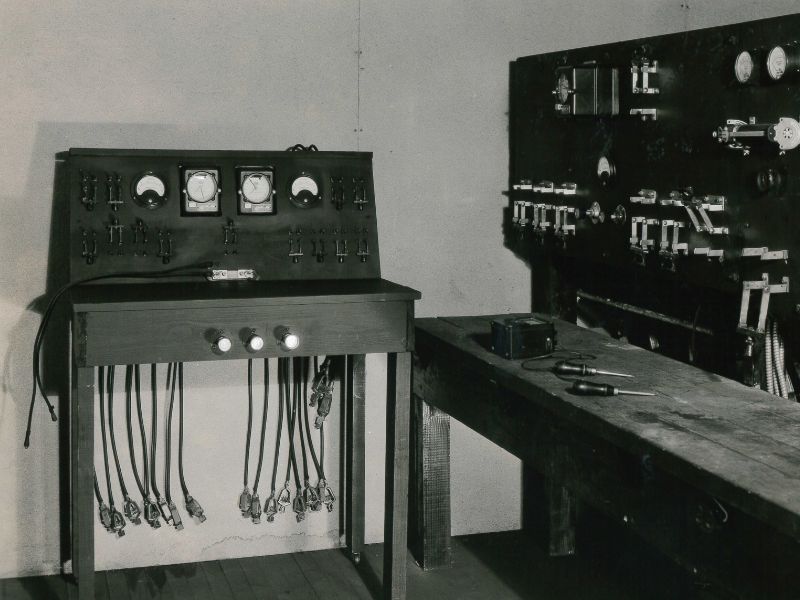

Back in Akron, Vernon was not looking for a job. He was looking for a way to bring one of his ideas to life. He wanted to create a service for measuring the electrical power required to run rubber factory machinery on a repetitive basis. He ran the idea by Albert Michelson, who was an executive at the National Rubber Machine Company in Akron. The two jumped from that idea to the concept of an independent service that would analyze the quality of tires. Michelson saw the promise of the idea, gave Smithers access to his Sweitzer Avenue garage, and Vernon decided to start a business. Smithers Laboratories was born.

Changes and Challenges

Using the laboratory equipment he was able to gather, Vernon began testing passenger car tires. He issued the first tire report in 1925 and more followed in quick succession. From the beginning, Vernon wanted to build client loyalty based on trust. His adage was, “If you are not certain it is right, don’t report it.” Within the first decade, the organization was doing business with nearly every rubber company in the United States.

Vernon’s tire testing was a first of its kind. From the beginning, Vernon refused free tires from tire manufacturers for testing. Instead, he purchased passenger tires that were available on the open market. The tests were extraordinarily detailed just as they are today, and were especially amazing given there was not a lot of technology supporting the type of testing Vernon wanted to do. Tests included the wrapping paper that covered all new retail tires, including the measurement and type of paper used, the general appearance, and more.

Once the exterior wrapping was tested and analyzed, Vernon’s testing methodology moved on to the tire itself. How did the tire look? Was it clean? Were mold marks properly aligned? Were letters well-centered and legible? Were bead wires properly insulated? All of this was recorded in painstaking detail.

The same testing standards were applied to the company’s testing service for tire inner tubes. The appearance of the tube was reviewed along with how thick the rubber was and whether that thickness was uniform throughout.

Around this same time synthetic rubber was emerging in the market. The Great War had shown that natural rubber was geographically limited and too much in demand to continue to serve the world’s appetite. Locally, Firestone, B.F. Goodrich, and Goodyear were all working on synthetic products.

Even though Smithers Laboratories was a new company, it was already growing quickly in this fast-changing environment. The development of synthetic rubber meant the company had to create new testing methodologies and invest in new testing equipment. In 1927, the company released its first Annual Tire Yearbook. In 1929, the company launched a new testing service targeting garden hoses.

The Great Depression

During the next decade, Smithers Laboratories would operate in a city where 60% of the workforce was unemployed. With the local rubber companies struggling financially while also battling with the new United Rubber Workers (URW) union (founded in 1935), it was clear Smithers Laboratories needed to seek service lines beyond tires and rubber. In a step that Smithers has repeated throughout its long history, the company pivoted.

Vernon decided to apply his testing methodologies to batteries, which helped supplement work from existing customers. Rubber companies had come to depend on Smithers Laboratories tire test reports, and even though their businesses were low on money, they continued to go to Smithers Laboratories for third-party testing, a testament to how quickly the young company’s reputation had grown.

Showing the trust that the rubber industry had in Smithers Laboratories, yet another new service launched during the 1930s. The company began to prepare tires for promotion. Customers for this service included manufacturers as well as tire retailers.

Across the Atlantic, the Research Association of British Rubber Manufacturers (RABRM) was also struggling through the Depression. A 1933 article in Nature Magazine discusses the “present plight” of the RABRM, later known as Rubber and Plastics Research Association (RAPRA). It was “a deplorable example of the results caused by an absence of any stabilised policy of financing industrial research,”6 the author argued.

While the RABRM was seeking more funding, a new organization called Printing Industry Research Association (PIRA) began. Meetings on the publishing, print, and packaging industries had been happening regularly since February 8, 1929, when a man named George Riddell presented “The Application of Science to Printing” at Stationer’s Hall, London. His presentation caused a buzz and was groundbreaking science at the time.

By April 1929, there were calls to create an official organization that would focus on “the collation of data, and the prosecution of scientific research into the problems of these trades.”7 By October 10, 1930, PIRA was an officially registered association. Like RAPRA, PIRA would play a major role in the Smithers story almost a century later.

In 1939, Smithers Laboratories was given an incredible opportunity to test four tons of smoked natural rubber sheets, which generated a 46-page report. Once again, however, the world intervened on the Smithers Laboratories path to success.

World War II Changes Everything

“I want to talk to you about war – about rubber and the American people,” President Franklin D. Roosevelt began in an address on June 13, 1942. “Rubber is a problem for this reason—because modern wars cannot be won without rubber and because 92% of our normal supply of rubber has been cut off by the Japanese.”

In response to the President’s call, US citizens were no longer allowed to buy new tires, whether for cars or bicycles. Rubber boots were out of the question. The government told Vernon that his tire testing services were not needed. They knew the quality of the tires and did not need new testing during wartime.

Not one to be intimidated by federal officials, Vernon went to Washington, D.C., to visit the Rationing Board in person. He presented the data his company had been methodically presenting and the importance of testing. Vernon won the debate. His lab continued to receive tires and other materials to test throughout the war.

Baby Boomers and Consumerism

Even after all of the turmoil in the world, by 1954, Vernon Smithers was becoming restless. Vernon, the intrepid entrepreneur, moved on to what would evolve into floral foam. He was excited about his new venture and invited his son Ted to come back home to help with the new company.

Meanwhile, in England, the Research Association of British Rubber Manufacturers moved to a facility in Shawbury, Shropshire. Today, this facility includes team members from Materials Science and Engineering and Medical Device Testing.

Oasis and a New Era

As Vernon Smithers began to formulate what is now known as the Smithers Oasis Company, he realized he could no longer invest the time he wanted to invest into Smithers Laboratories. He began to seek a buyer, and he came upon a young man named Bob Dunlop. Dunlop was born and raised in Northeast Ohio. He earned his BS in Mechanical Engineering from what is now Cleveland State (it was called Fenn State in 1939).

In 1950, Bob left his testing job at B.F. Goodrich and began his own consulting firm. He happened to meet Vernon when they were both analyzing tires in Des Moines, Iowa. Bob impressed Vernon, and later, while wondering to whom he should sell, he called up Bob. After a whirlwind business trip to Europe, Robert came back to Vernon and said that all he could afford was $20,000. Vernon counteroffered. “For a down payment, you may pay me $10,000 and keep the other $10,000 for your operating expenses.” The deal was closed. Bob Dunlop took over as president of Smithers Laboratories on July 1, 1955, 30 years and a few weeks after its founding.

The company Bob acquired was small. After making it through the Great Depression, World War II, and the chaos that had ruled the rubber industry, Smithers Laboratories was ready to ride the tail of consumerism and enter a time of stability. Over the next decade, that is just what would happen.

- The First Thirty Years: 1925-1955

- Building Upon a Trusted Brand - Evolution: 1956-1975

- Resilience and Expansion: 1976-1985

- Beginning of a New Era: 1986-1990

- Diversification and a New Era: 1991-2005

- A Flurry of Growth Activity: 2006-2011

- Expansion in the Life Sciences: 2012

- Organic Growth Period: 2013-2017

- Unity, Growth, and Resilience: 2018-2020

- Pushing the Boundaries of What is Possible: 2021-2024